I recently had two very different but connected experiences. The first was encountering ancient rocks in the geology exhibit at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. The second was watching a film about concrete at The Robert Burns Centre in Dumfries.

In Italy, the land of Carrara marble and Michealangelo, there is a rock industry on a crushing scale – pulverising mountains to make aggregate for concrete manufacture. This film shows in mesmerising slow mo the destructive spasm of millions of tonnes of rock blown apart by exposives to make that most mundane of building materials – concrete. In juxtaposition we see concrete apartment blocks in Ukraine and Turkey, smashed open by war and earthquake respectively. What took millions of years to form as a timeless feature of planet earth is made into disposable units of pointless rubble. Or should I say non-disposable, as that is the point too.

“When we design something we design the behaviour of people” says Italian architect Michele De Lucchi in the film. Put this together with the fact that concrete production creates 8% of all CO2 pollution on earth and we start to get at the contemporary dilemma of confusing creation with destruction. It is simply unsustainable to keep making concrete buildings, but we are on a mad trajectory of self-delusion where tourism alone accounts for 8% of the world’s carbon emssions (Sustainable Travel International).

The Cambridge Dictionary defines infinity as “time or space that has no end” and we live our lives with the assumption that this is a real concept, one which can be relied upon to structure our existence from morning until night, and in between. Otherwise we would fear falling sleep every time and routine activities would take on cosmic uncertainty – how could we rely on the joy of human knowledge and the expectation of future wisdom? Admittedly there are plenty of world leaders who make us quesion these things – but that’s surely the point. We know that the lies of leaders create a rupture in the fabric of shared knowledge and hope for a better future which we all still seem to strive for.

Soon after viewing this powerful film I found myself in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, specifically the geology section.

Now there is a number beyond the scope of the human brain – who could ever prove it as accurate? It’s an estimate on an epic scale, a wildly creative figment of scientific imagination freefalling into an ecsasy of transcendent reasoning. Or at best, an informed suggestion of what infinity could look like.

Radiometric dating is pretty good for ageing old rocks but the sheer numbers defy our imagination for understanding what they might mean. Everything becomes a relative unit of comparison with another theoretical number which leaves our capacity for mentally grasping these numbers a cognitive irrelavance. We have become used to hearing these vast numbers without really knowing what they mean; we must trust in the wisdom of scientists and mathematicians to have the knowledge behind the knowledge. This is called faith in my book, and we should acknowledge the fact. Faith in science’s ability to describe and know infinite ideas by numbers.

But infinfity is not about numbers. It is about escaping the world of the finite, and numbers are only a crude way of illustrating this concept.

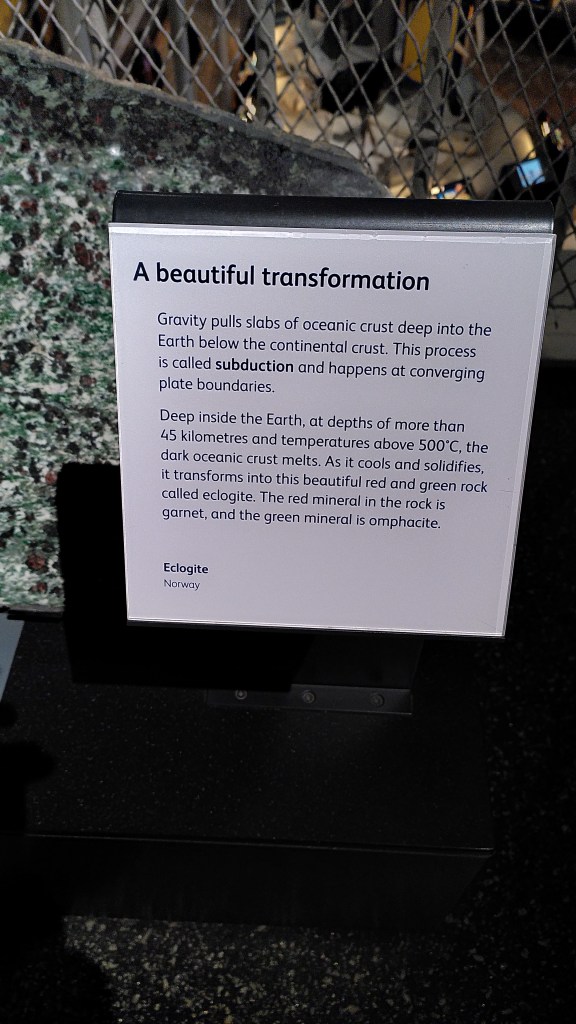

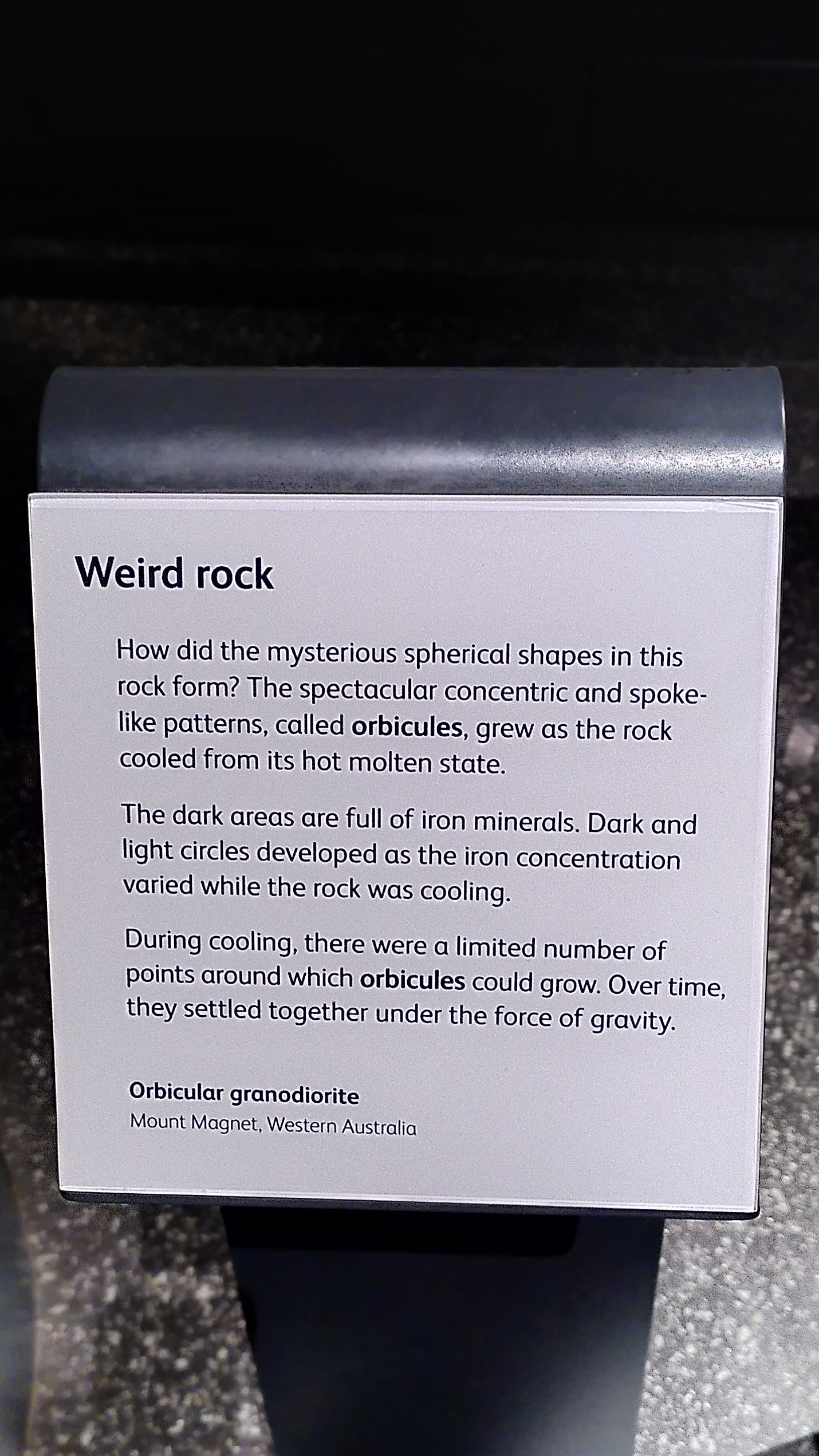

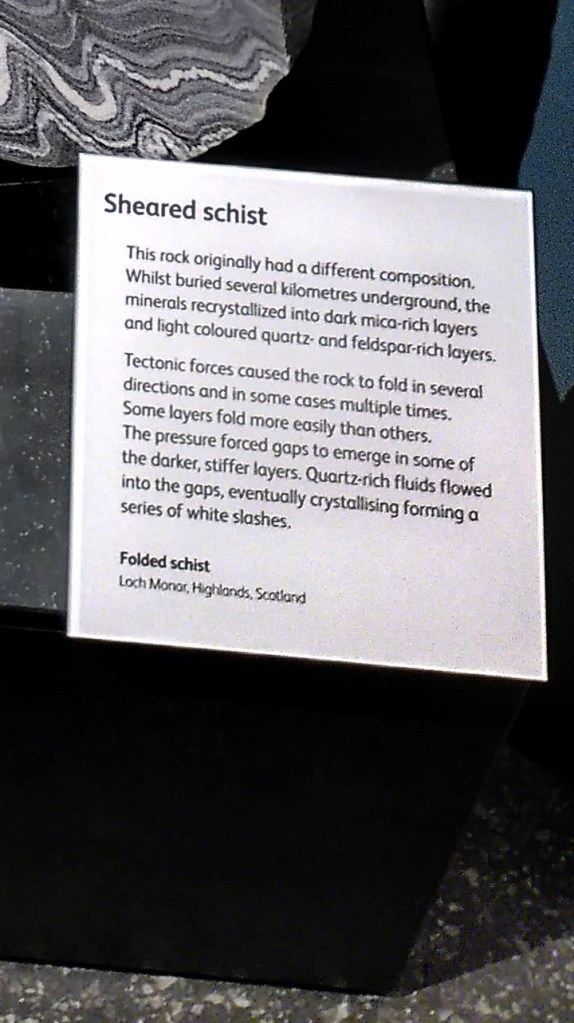

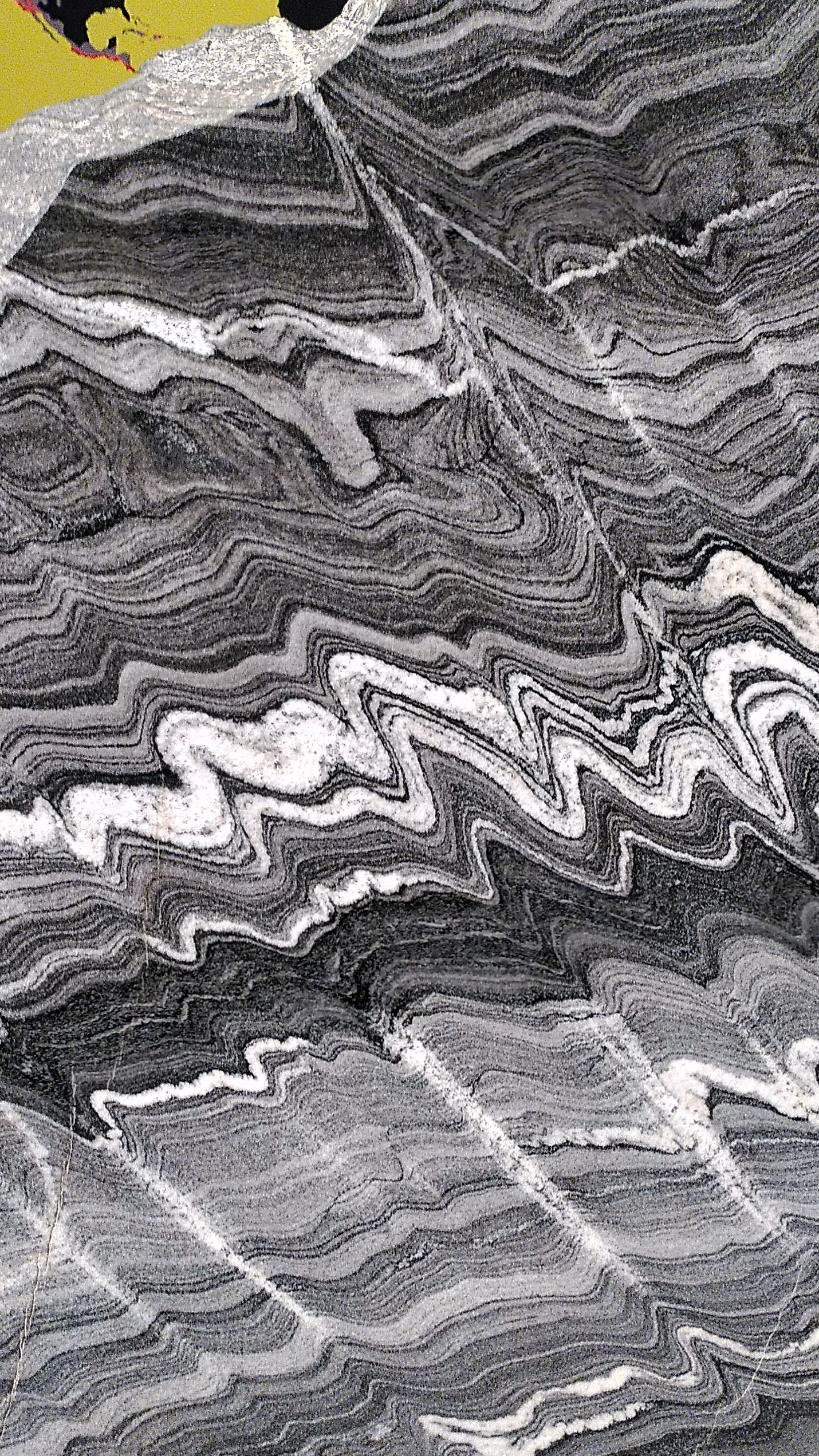

At a certain point in the process of time, beauty takes over from quantity and produces evidence of the contiuum we call infinity. The surface of ancient rock removes us from the geological upheaveal and confronts us with an established fact in front of our eyes. Do we need to know how long it took to be able to respond to that beauty?

Yes, we should always ask how things were made or what physical processes caused other physical processes to come about. But are we looking for proof of something else? Something beyond the physical evidence, something that the evidence is proof of?

The relationship between force and flow is something beyond an easy explanation. Yet we can see it in the shapes and patterns of this rock. It exists as evidence of forces caused by the earth deciding to upheave itself at a time in history. Like a seismogram, it illustrates amazing forces which a geologist can imagine from knowledge of timescales and rock movement.

According to Stephen Hawking, “The usual theory of eternal inflation predicts that globally our universe is like an infinite fractal, with a mosaic of different pocket universes, separated by an inflating ocean.” * Given that we live in a world of metaphors (or mentally trapped in Plato’s cave if you prefer it), this one is great at linking aesthetics with science without even trying. The infinite fractal is an endless beauty which leads somewhere which we can never know because our senses cannot go there. Like a Dali miniature, painted with a one hair brush, we are drawn irresistably into a world which only existed in Dali’s mind.

Dali saw himself as God, and in this sense he was right – the world exists beyond the senses of man, in an ininity of numbers and ideas beyond proof or contradiction. But he was wrong in claiming that territory for himself beyond his own created universe and calling himself the Creator. That is actually blasphemy.

Salvador Dali – The Weaning of Furniture Food, 1929 – Poetics of the Small exhibition, Meadows Museum, Dallas, 2018. (Reminds me of Plato’s Cave somehow)

*Interview with Hawking, 2 May 2018.